Feature article by Tom McDonough with a portfolio of some of my earliest black & white photographs most made in the early 1970’s while I was still living in my hometown, Utica, NY. Thank you Tom & OSMOS Magazine.

UTICA GLASS

Tom McDonough

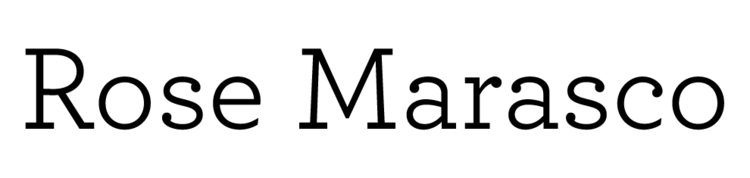

At first glance, the photograph captures a straightforward example of vernacular commercial architecture. The façade stands at a slightly oblique angle to the picture plane – a choice, one imagines, made to better capture the reflection, in the large display window that dominates the ground floor, of buildings standing across the Street: three nineteenth-century homes and, as our gaze continues into the distance to the right, some larger buildings with shops at street level and apartments above; behind them, the towering smokestack of the Utica Club brewery punctuates the sky. The window becomes a mirror, collapsing the street scene onto its flat surface. Above this reflected streetscape, the name of the company appears in dark uppercase letters against the white metal panels of its renovated frontage: “UTICA GLASS.” Many of the concerns that define the youthful work of Rose Marasco, who took this photograph in the early 1970s in the upstate New York city of Utica, are present in this deceptively modest image. She has a particular eye for the urban landscape, for shopfronts especially, and what could be seen through, or reflected in, their display windows. She also has a keen affinity for the play of found language, as here, where UTICA GLASS names both the owner of the property – still there today on Varick Street – and the subject of the image: Utica, on glass. One might also detect a self-reflexive nod to photography itself, with the cityscape mirrored in the window much like it would be in the lens of the camera. And, of course, there was her fascination with the scenes offered up by this city above all, captured as she wandered the streets of its neighborhoods – a fascination not with so much the people to be found on them, which would come later, but with what their physical appearance offered up. We in fact seldom find humans animating her pictures of these years, and when considering this, we might notice that the oblique angle at which she shot Utica Glassguarantees that the photographer herself would remain invisible, just out of view.

Marasco was only in her twenties when she took this, and many other striking photographs, of her hometown of Utica, which sits just off the New York State Thruway about halfway between Syracuse and Albany, in the Mohawk Valley. She had grown up there, in the heart of the city’s Italian-American east side, raised after her father’s early death by her mother and maternal grandmother. An early interest in art had led her to study advertising design at the local community college, and then, from 1969 to 1971, to complete her BFA at Syracuse. When she began there, Marasco was studying graphic design but quickly found its professionalized atmosphere unappealing amid the freewheeling upheavals of the late ‘60s; she would be more at home in the university’s so-called “experimental studios,” a home for the art school’s misfits, where students were encouraged to work across media. She took printmaking courses, made 8mm films and animations of her drawings, but even amid this permissive atmosphere, no photography courses were to be found. For that, Marasco had to get permission to go to the School of Journalism, which offered classes on photojournalism. She had been taking pictures since her childhood, when she had borrowed her parents’ Brownie and photographed the intimate world of the family; after her two years at Syracuse, she returned to Utica and, with a used Argus C3 – later replaced, once she could afford it, with a Nikkormat – began roaming the city’s streets, searching out less familiar images.

Jessica May, who organized a recent retrospective of Marasco’s photography at the Portland Museum of Art, describes the resulting works in this way: “When she turned to making photographs as a young artist, she was drawn to the images in the world around her, yet her primary interests were formal: Marasco drew on the photographic ideas of perspective, graphic dynamism, and contrast of forms to create images that hovered between everyday life and an abstract rendering of form in space.” Indeed, under her gaze the everydayness of Utica is transformed into something surprising, made unfamiliar through point of view, cropping, and abstraction. The language of commercial signage is fragmented into purely phonetic-compositional elements, as in DA, Utica(early 1970s), with its remarkable play of inky depth and planar frontality. We are reminded of her precocious interest in printing technology, her love for handset type, explored on the linotype machine at Mohawk Valley Community College. An appreciation for the materiality of language comes through again and again in these early photographs, but so too does a clever play with found poetry: “FRIENDLY,” declares storefront signage in a wintry nighttime shot, but that is a promise belied by the handwritten “CLOSED” notice posted in the window; a placard reading “SLEEPING ROOMS” warns off potentially disruptive pedestrians in a window punctuating a brick wall. Elsewhere, the play of reflections captures Marasco’s interest, like in Utica Glassor another obliquely shot storefront, a barbershop whose large front window is transformed into a mirror of the bare trees across the way. And abstraction enters the work through a careful attention to doubling, a sort of allegory of photography’s reproducibility: of garage doors in Gas Station Doors, NY(early 1970s); of wooden chairs set at the entrance to a shuttered store; of restroom doors on the side of a building; of the Utica Club slogan, spotted in a window: “One good thing ... leads to another.”

This is not to say that Marasco’s Utica photographs are devoid of sociological interest. She was consistently drawn to the city’s shopfronts – the modest mom-and-pop commercial landscape that still survived from the early twentieth century, not yet replaced by national chains and the suburban strip. We find this vernacular, with its handmade signs and quirky window dressing, pictured repeatedly in these years of the 1970s, most beautifully perhaps in the color photograph Barber Shop, Utica, NY(1974). The spirit of Walker Evans haunts such work, both in its loving attention to these overlooked spaces and in its lingering melancholy. It’s important to recall that Marasco was a native of this town, had grown up there within the bounds of family and neighborhood, the tight-knit world of the Italian-American east side. The camera gave her permission to explore, to expand the boundaries of that world, to roam the diverse neighborhoods, presumably early in the morning, when no one else was about. These early works picture a Utica stripped of family history, of the specificities of an ethnic past, and reimagine it as a site of modernist experimentation. They are, in that sense, not only documents of the city at a moment of transition, but also of Marasco as an artist in the making.

To support herself, she turned to various jobs, first at Kirkland College in nearby Clinton, NY, where she worked as interim director of publications and then, from 1974, at Utica’s Munson Williams Proctor Art Institute, where she founded a photography program in the School of Art, building its curriculum, setting up its studios and darkrooms, and teaching there for the next five years. It was at the MWPAI that Marasco would meet Nathan Lyons in the mid-‘70s; with his encouragement, she began taking summer classes at the Visual Studies Workshop, then still a fledgling program Lyons ran with his wife Joan in a former warehouse in Rochester. The lessons absorbed at the VSW would inform the next phase of Marasco’s work, as she introduced more narrative and durational elements into her photography, something already hinted at in the triptych Woman with Scarf, Rome, Italy(1976) and further developed after her move to Portland, Maine, in 1979. Her practice over the next forty years attests to the richness of her vision, but the years in Utica are more than a mere prelude to this later work – what she made there over a short decade between 1971 and 1979 captures this city as a space of visual inventiveness, formal experiment, and personal discovery.